In Reading a Feed Tag (Part 1) we discussed basic items required on feed tags and their implications to feed quality and consistency. In Part 2 we are going to discuss guaranteed analysis and ingredient evaluation in more detail.

Mare Distler

Merging Guaranteed Analysis and Ingredients

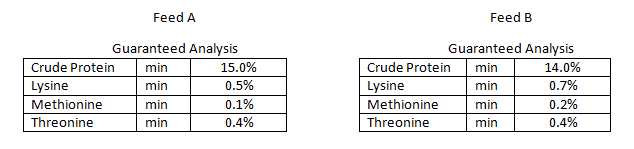

Crude Protein: Crude Protein guarantees provide an estimate of the amino acid content of a feed. Horses require specific dietary essential amino acids (building blocks of protein that they cannot make themselves) as well as a certain level of total protein to provide the building blocks for other amino acids that they can make on their own. The level of dietary essential amino acids in a particular protein source provides an estimate of “protein quality” of that protein source. The four dietary essential amino acids that equine nutritionists are most concerned with include Lysine, Methionine, Threonine and Tryptophan. These four amino acids are also commercially available to be individually and separately added to horse feeds in order to improve the overall amino acid balance and protein quality of the feed. Lysine level of the feed actually gives a much better indication of how well that feed is going to meet my horse’s amino acid requirements rather than crude protein by itself. Consider the following example:

Feed A contains more crude protein than feed B, therefore, if that was the only nutrient guarantee provided you would assume that feed A would be a better choice for growing horses or horses working at intense levels. However, when you compare the dietary essential amino acid content of the two feeds you notice that feed B contains more lysine, more methionine and an equivalent amount of threonine as feed A. Due to the greater concentration of these dietary essential amino acids, feed B is actually the better product for growing horses and horses working at intense levels.

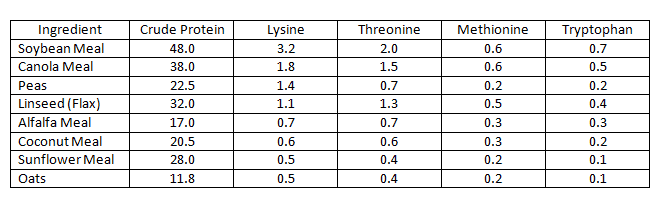

How can feed B contain more dietary essential amino acids if it is actually lower in crude protein content? There are two possible reasons for this: 1) Feed A utilizes a protein source that is high in protein but low in dietary essential amino acid content and/or 2) Feed B incorporates the inclusion of individual amino acids in combination with a good protein source to increase the levels of these specific dietary essential amino acids. Incorporating individual dietary essential amino acids is a good formulation practice because it can improve the overall balance of protein and amino acids which in turn increases the efficiency with which your horse utilizes protein for growth and performance. Table 1 provides crude protein and dietary essential amino acid content for common protein ingredients used in horse feeds.

Table 1. Select amino acid composition of common ingredients used in horse feeds.

Table 1 illustrates that soybean meal not only provides the greatest amount of total protein but also supplies the greatest amount of all four dietary essential amino acids. The level and balance of dietary essential amino acids in soybean meal comes the closest to matching the “ideal” balance of all plant based protein sources for horses; this is the reason that the use of soybean meal in equine diets is so common. Some horse owners prefer not to feed soybean meal to their horses for various reasons (some reasons are valid and some not so much). In such cases extra care must be taken to ensure that dietary essential amino acid requirements are met. For example, relying on the use of peas or coconut meal to supply needed amino acids may leave your horse deficient in threonine and methionine if these individual amino acids are not included separately in the feed formulation.

Crude Fat: The inclusion of fat (oil) in horse feeds is a relatively new practice. Thirty years ago a horse feed containing 5% crude fat was considered a high fat horse feed and equine nutritionists were questioning if a horse could even utilize that much fat efficiently. Today it is common to find horse feeds containing 10% or more fat. Once research demonstrated that horses can in fact utilize 10 – 12% fat efficiently the practice of adding relatively high amounts of fat to horse feeds became commonplace. The objective of adding more fat to horse feeds was to provide an adequate amount of digestible energy without having to feed large amounts of grain high in starch. Initially, this was thought to improve stamina and temperament, but also proved to be an effective way to reduce problems associated with tying-up as well as making it easier to manage horses presenting with laminitis and geriatric horses.

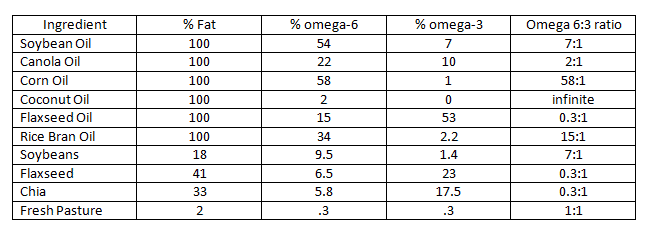

Horses have a dietary requirement for two fatty acids, 1) linoleic acid and 2) linolenic acid. These two fatty acids cannot be made by the horse and must therefore be present in the horse’s diet. Fortunately, both of these fatty acids are normally found in fresh forage such as pasture grass. Horses without access to fresh forage should receive a diet that provides both of these dietary essential fatty acids. (Note: linoleic is an omega-6 and linolenic is an omega-3 fatty acid). Higher fat levels in horse feeds are often achieved by including vegetable oil and/or high fat seeds such as full fat soybeans, flaxseed or chia. Table 2 compares fat levels of common oils and high fat seeds used in horse feeds.

Table 2. Fatty acid composition of selected ingredients often found in horse feeds.

Table 2 illustrates that not all oil sources are created equal in their ability to provide the dietary essential fatty acids in the proper amounts and ratios. The preferred omega-6 to omega-3 balance (ratio) is less than 10:1. Research with horses has not proven an advantage to a ratio of 2:1 versus 10:1 for example, but has demonstrated a physiological difference between 10:1 and greater than 20:1. Based on these guidelines, examination of Table 2 illustrates that corn oil, rice bran oil and coconut oil do not provide the proper balance between omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids and are therefore not preferred sources of essential fatty acids for horses. That is not to say that they do not have other positive attributes but those qualities should be considered secondary to the dietary essential fatty acid composition. In other words, it is acceptable to provide rice bran oil to horses but only after linoleic and linolenic acids have been properly balanced.

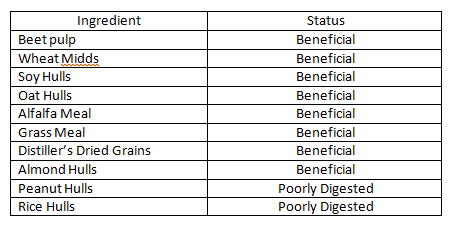

Crude Fiber: Crude fiber really does not tell you very much about the quality or nutrient content of a feed without also examining the ingredients that make up the majority of the crude fiber value. Crude fiber can be used as a rough estimate of the digestible energy content of a feed but only in the most general terms. Generally speaking, the lower the fat level and the higher the crude fiber level the lower the digestible energy content of the feed and vice versa. More importantly in my opinion is the ingredient composition that makes up the crude fiber component of the feed. Some fiber sources are quite digestible and others are not. Ingredients that have poor digestibility tend to be cheaper, more inconsistent and may contribute to digestive disorders. Table 3 lists fiber ingredients found in horse feed and identifies them as being beneficial or poorly digestible.

In my opinion, the one ingredient that is most misunderstood is wheat midds or wheat middlings. Wheat middlings are not so much a “by-product” as they are a “middle product”. Wheat is milled into flour – most people understand what flour looks like (wheat flour = wheat starch) and most people understand what a wheat kernel looks like. During the process of turning wheat kernels into flour the non-starch components of the wheat kernel are separated from the starch – this fraction is what is referred to as wheat middlings because they are generated from the middle of the process that converts a wheat kernel into wheat flour. This process is completely mechanical and does not involve any chemical extraction. Wheat middlings are a good source of protein, fiber and B-complex vitamins that also contain a low NSC content. Wheat middlings are also quite palatable and digestible for horses. This is why they are a common ingredient, especially in pelleted horse feed products.

Table 3. Fiber sources found in horse feeds.

Minerals and Vitamins: As indicated in Reading a Feed Tag (Part 1) the minerals and vitamins required to be guaranteed on a horse feed label include Calcium, Phosphorus, Copper, Zinc, Selenium and Vitamin A. Many feed companies elect to voluntarily include additional minerals and vitamins in their guarantee listing in order to provide their customers with as much reasonable information about their product as possible. For example, a person who manages a horse with HYPP would be concerned with potassium levels, or a person with an IR horse may be interested in knowing what the iron level of a particular horse feed is.

Because every horse’s diet should be based on forage (pasture and/or hay), the mineral content of a feed should complement the mineral content of the forage. For example, the major source of potassium in a horse’s diet is pasture or hay, not a supplemental feed product. Therefore, if you are concerned about your horse’s potassium intake you need to be aware of the potassium content of any forage your horse is consuming. Yes, you should still be aware of the potassium level of your feed but place the emphasis on your forage. On the other hand, the majority of many trace minerals such as selenium, zinc and copper will be supplied from a feed product more so than your horse’s forage intake, this is why these minerals are required to be guaranteed on a horse feed product label.

Trace minerals can be supplied from minerals salts such as copper sulfate or organic sources such as copper proteinate or a combination of the two. Clinical and research trials suggest that organic mineral sources provide certain physiological benefits that mineral salts do not, especially when a horse is experiencing greater than normal levels of stress. Selenium yeast has not only been proven to be more physiological available compared to sodium selenite or selenate but is also less toxic making it a superior source of selenium for your horse.

Horse owners of insulin resistant horses are sometimes concerned with excessive iron intake since excess iron may exacerbate insulin resistance. Keep in mind that excess iron does not cause insulin resistance, but may increase insulin resistance in individuals already affected. Other items to keep in perspective include: 1) many forages and feed ingredients naturally contain iron levels greater than required to meet the horse’s iron requirement, 2) excess iron exacerbates insulin resistance most when it is out of balance with copper, zinc and manganese. Therefore, keeping these four minerals within a certain range (balance) reduces any negative effects of excess iron in regard to insulin resistance, 3) most iron naturally found in forages and feed ingredients may not be digestible and therefore poses a minimal problem for an insulin resistant horse, 4) even if iron is not included in the guaranteed analysis the amount of iron in any feed product is likely to be similar to any other feed product that does guarantee iron on the product label, and 5) if you do have any questions or concerns about the iron level of your horse’s diet it is usually best to consult with a trained equine nutritionist to determine if any adjustments should be made to your horse’s diet.

Miscellaneous Ingredients and Guarantees: Some horse feed products may include probiotics, prebiotics, digestive enzymes and other non-nutrient additives and will guarantee the levels of these ingredients on the product label. Most of these miscellaneous ingredients are included for the purpose of supporting normal digestion and intestinal health in the horse. These ingredients, when ingested by a horse will either help or do nothing. For a horse at maintenance that presents with normal body weight and normal health these ingredients are usually not needed. However, horses with sensitive digestive systems and horses under stress for whatever reason usually receive some benefit from ingesting these ingredients.

However, keep in mind that there does appear to be a minimum amount to be effective. For example, separate research recently reported by the University of Kentucky and Ohio State University indicates that at least 1 billion or more colony forming units (CFU’s) of an individual probiotic is required to effectively alter the microbiome in a horse. Mixing several different strains of probiotics that total 1 billion CFU’s will not be as effective as a single probiotic strain fed at 1 billion CFU’s per day. Therefore, read the product label carefully if you desire to provide your horse with the benefits of probiotics and prebiotics to be sure the amount provided will in fact be sufficient to be effective.