To compete at the Thoroughbred Makeover, each horse must pass an arrival exam, which includes scoring 4 or higher on the Henneke BCS scale. Photo courtesy Margaret Burlingham

The topic of body condition is a hot one for owners of off-track Thoroughbreds. “He’s just a little too thin,” or “I wish I could keep weight on him,” or “I can still see his ribs” are common sentiments. But what does “too thin” mean? To complicate matters, thin can look vastly different depending on a horse’s breed and discipline. It’s why veterinary professionals, equine nutritionists, scientists and organizations like the Retired Racehorse Project use the nine-point Henneke horse body condition scoring system as a more objective way to measure the amount of fat on a horse’s body.

So what exactly is a body condition score (BCS)? We asked Shannon Pratt-Phillips, PhD, a professor of equine nutrition and physiology at North Carolina State University, in Raleigh, and Bob Coleman, PhD, associate professor and equine extension specialist at the University of Kentucky, in Lexington, to explain the purpose of a body condition score, how horse owners can use the Henneke system on their own horses and how to help horses reach an ideal score.

In essence, the “body condition score is the easiest way to figure out if a horse’s calorie intake is sufficient to stay healthy and perform their job,” says Pratt-Phillips. “Calories are the only dietary component where you can look at a horse and say, ‘You’re getting excess’ or ‘You’re not getting enough.’ ”

The Henneke BCS scale is also a good tool to help owners monitor horses’ overall health. “If there’s an underlying condition, like poor dentition or parasites, body weight is one of the first things where you might see a change,” says Pratt-Phillips. “If you know what your horse’s score is at a baseline, it’s easier to monitor them for changes.” (Find descriptions and illustrations of each score at TheHorse.com/137703.)

“Ideal” body condition lands in the 4-6 range, based on research performed at Texas A&M University. “Researchers asked the question, ‘What is a reasonable range for an athletic horse that allows them to perform their job?’ ” explains Coleman. “What came out of that research is that if they’re between 4 and 6, they have the body stores and the energy that allow them to perform a job, and they can also thermoregulate. If they’re less than a 4, they won’t have body fat stores to draw on for calories to do a job, so they simply won’t be able to keep up.”

On the other hand, horses that score greater than a 6 struggled because they could not cool off. Coleman likens being on the upper end of the BCS range to trying to clean stalls wearing a big coat: You’ll get tired and hot sooner than anyone else, and it will be harder for you to get the job done.

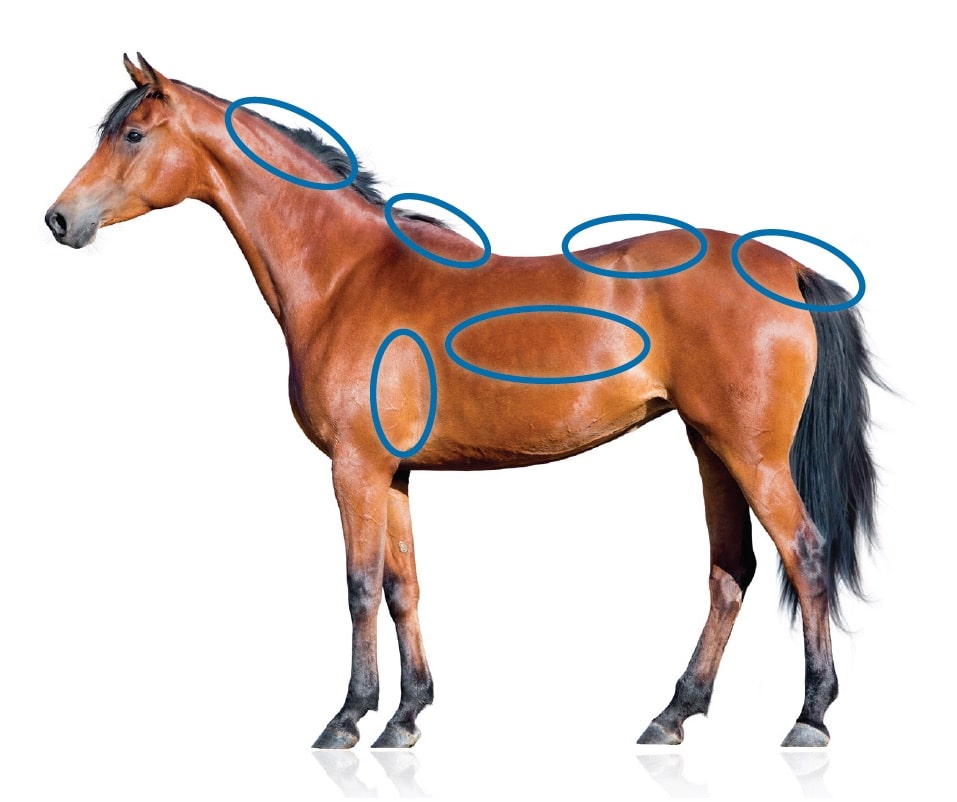

When scoring your horse, focus on areas where fat tends to deposit: the rib cage, behind the shoulder, the withers, over the loin, the tailhead and the neck crest. Getty Images

Pratt-Phillips recommends assessing your horse’s body condition score with a friend’s assistance. “It can be helpful to score someone else’s horse versus your own because a lot of the time you can be biased against your own horse,” she says. “Owners are usually less critical of their horse’s score than someone else is.”

Hundreds of videos and countless articles online can walk you through the steps it takes to score your horse. It’s very important to both look at your horse and take the time to palpate key areas on his body: the ribs, shoulder, withers, loin, tailhead and neck.

“You have to get your hands on the horse in order to score them,” says Coleman. “You should be feeling the fat deposits. When I score a horse, I start at the neck, run a hand across the shoulder and straight over to the hip. I ask, how easily can I feel their ribs? Next, feel their back: Is their backbone sticking up? If so, how much is it sticking up? If there’s a bit of a positive crease, that means there’s more fat on their back. Next, I run my hand down their loin and feel along the tailhead to see how much it’s covered up.”

So what do you do if your horse falls below a 4 on the scale? What if you’ve recently purchased an OTTB and are already struggling to put weight on him? Horses coming right off the track are typically super fit and all muscle. On its own, muscle burns more calories than fat, so the maintenance calorie needs of a newly retired racehorse will be higher than those of a less-muscled horse of comparable weight.

“If you have two horses that weigh 1,000 pounds, and one is sheer muscle and the other is a 14.2-hand pony that’s really fat, the calories they need are going to be different,” explains Pratt-Phillips. “Sometimes being on the track and living that lifestyle can make ex-racehorses more high-strung and add stress. This can create behavior issues like cribbing, weaving, stall-walking and pacing, and all of those behaviors and higher anxiety levels will burn more calories.”

Coleman emphasizes that while every horse needs to be evaluated as an individual, the math is the same when it comes to trying to add body condition and preparing for their new careers. That starts with looking at their calorie intake through three lenses.

“First, we need to meet their maintenance requirements,” he says. “If they need X number of calories per day to maintain condition, we have to meet that number first. Then, if you want them to gain weight, we need to add X more calories. And finally, if they’re doing light work for retraining purposes, we’ll need to add X more calories to replenish what they’re burning there. We can’t just feed for work.”

Pratt-Phillips says it’s safer to increase the amount of fiber and fat you’re feeding than sugar/starch intake, because the latter can lead to an increased risk of colic and gastric ulcers. You can add fiber in the form of free-choice higher-quality, less-mature hay, which has more calories per unit of weight.

“Also look into beet pulp and rice bran since they are high in fiber and fat,” she says. “Oils and fats have twice the amount of calories when compared to carbohydrates, and oils won’t impact your nutrient ratios as much since it’s just calories.”

When adding oil, Pratt-Phillips recommends starting with 1 tablespoon per day and increasing from there; most horses can tolerate 1 cup per day easily. But keep an eye on their poop — if it becomes shiny, it means they’re getting too much.

Coleman recommends adding 5-8 pounds per day of a concentrate with a high amount of soluble fiber (e.g., beet pulp and soy hulls) and fat content that’s at least 8%. You might also consider adding a high-fat supplement. “Most are between 25-40% fat,” says Coleman. “These are great when fed at a rate of 1-2 pounds/day, and they work quite well.”

Keep meal sizes to no more than 5 pounds per feeding to reduce the strain on the digestive tract; Pratt-Phillips and Coleman both caution against feeding high volumes of cereal grains and commercial grains because some are higher in simple starches that can affect the sensitive, ulcer-prone gastrointestinal tracts of OTTBs.

If you’re having trouble improving your horses’ body condition, Coleman recommends making sure they’ve had their teeth done and been checked for ulcers, which can cause erratic feed consumption. “You can also add alfalfa,” he says. “From a research standpoint, alfalfa does a good job at providing additional acid-buffering so it will not only prevent but can also help with recovery from ulcers.”

Your work isn’t over once your horse has reached that minimum 4 score required to compete in the Thoroughbred Makeover. “Once you get them to the condition where they look good, you should add a little more condition,” says Coleman. “The stress of transportation and the physical work of simply being on a trailer can take a toll on them and cause weight loss. And you don’t want to show up in Kentucky with a horse that went from a 4 to a 3.5 because they lost weight during travel.”

In the end, adding condition to any horse, especially an OTTB, simply takes time. “Horses aren’t designed to gain a lot of weight in a hurry,” says Coleman. “These horses are learning to do something else, they have a new career and they’re acclimating to a new environment. Slow and steady will win the race.”