How to keep tabs on your favorite racehorses, and best practices for buying a horse at the end of its racing career

Jen Ruberto kept tabs on I Am The King, a horse her family owned as a 2-year-old, throughout his 97-race career: “I followed him through five or six trainers,” she recalls. “I contacted each one of them to let them know I really wanted to be the one to find him a home when he retired. Some trainers were tough to track down, but eventually I spoke to each of them many, many times to remind them this horse was special and he had a place to go. He retired at 13 years old, looking amazing, and he rode just like he did the last time I galloped him 10 years prior. He is now a dressage horse in mid-Ohio.” Courtesy Jen Ruberto

If you’re like me, a trip to the racetrack is typically filled with a few bets, lots of fun with friends and an inordinate amount of, “Oh, look at that one! He’d make an awesome eventer!” Then, of course, I start tracking his career and I research his connections, keeping them in mind if I find myself with an open stall when the horse’s racing career starts to slow. One can never be too prepared, right?

While I’ve never followed through on bringing home one of the prospects I’ve picked on the track, many people do. It’s one way equestrians secure their next OTTB, but the process might seem daunting if you’ve never tried it. In this article two horsewomen with plenty of experience in the area — Jazz Napravnik, a flat and steeplechase trainer who also retrains Thoroughbreds for second careers in Monkton, Maryland, and Jen Ruberto, who runs Wire to Wire Sporthorses, in Lisbon, Ohio, and is actively involved in her family’s racing stable — share their tips for transitioning from admirer to owner.

Step 1: Pick Your Prospect

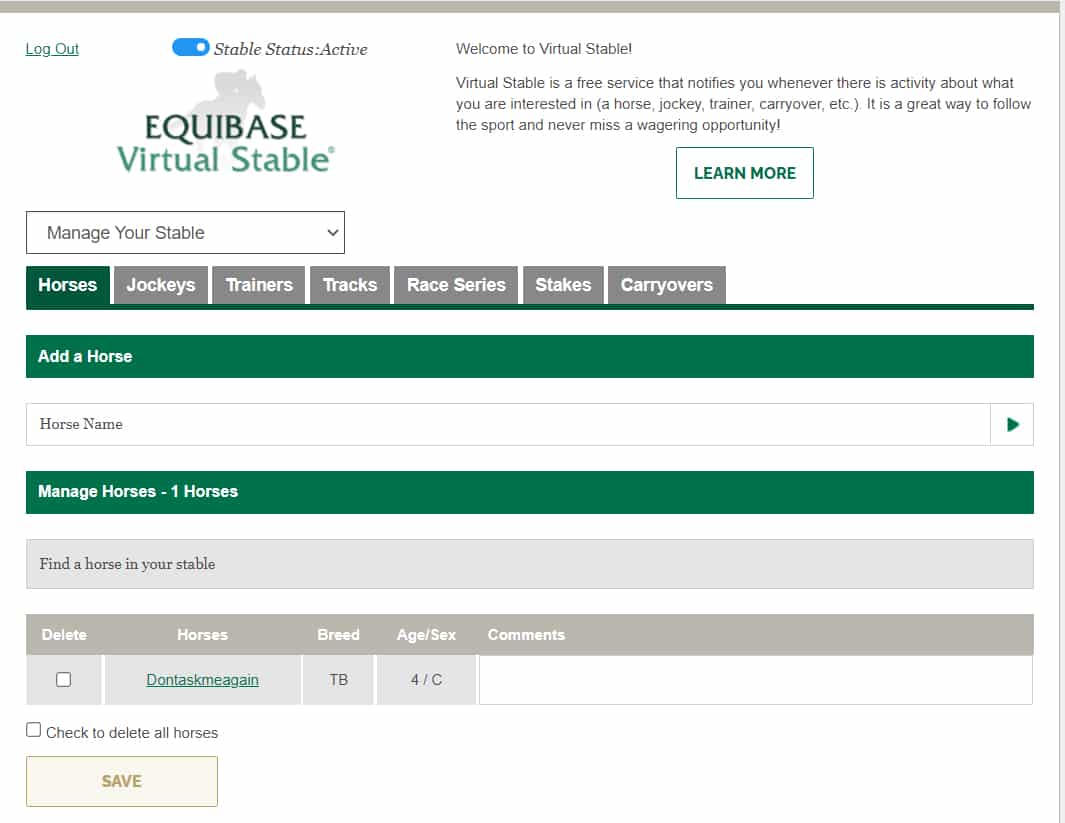

It might be a certain look, a conformational trait or the perfect gait for your discipline of choice. Whatever the reason, you’ve spied a horse in the paddock or on the track you ’d love to make your own. An easy way to follow his career is to add him to a virtual stable on a site such as Equibase, Brisnet or TVG. You must create a free account, but you’ll get notifications every time the horse works or races and alerts with race results. You can also use such sites to learn more about him.

“I usually research the horse on Equibase to see who the racing connections are,” Ruberto says. “Since I’m already connected to the racing industry, I see if I know the trainer and, if not, I see if I know anyone at the track where that horse has been racing.”

She says she typically contacts the horse’s trainer first, as does Napravnik.

“If someone already has a connection with the owner, by all means, they can contact them,” Napravnik says. “But if it’s someone outside of racing completely who sees a horse and thinks, ‘He ’d be a really nice sport horse,’ I ’d contact the trainer first.”

Google can help direct your next steps. Some trainers have websites with contact information. If not, call the racing office at the last track where the horse ran (also easy to find via Google), and ask for the trainer’s contact information, says Napravnik.

“Some will give it to you, others won’t,” she says. “If they don’t, I ask them to pass a message along to the trainer with your contact information. It’s not foolproof, but I’ve certainly gotten horses that way before.”

And don’t be afraid to ask the masses, Ruberto says: “Take to social media! Most connections are on one of the several (social media platforms). If they’re not, there are tons of groups on Facebook where you can connect with thousands of Thoroughbred enthusiasts. Usually someone will know the person you are looking for.

“I think the best way to contact a trainer is by email, text or Facebook message,” she adds. “By doing this you will not bother them with a phone call during training or racing hours, and they can get back to you during less busy hours.”

Just as you would with anyone, be mindful not to text or message too early or late in the day, she says.

Don’t be afraid to be persistent. “If you don’t hear back within a few days, try again,” Napravnik says. “Random people are not typically a trainer’s top priority, but the squeaky wheel’s going to get the grease. They think, ‘Wow, this person’s serious. Maybe I’ll take them more seriously.’ ”

Avoid contacting people too frequently. Understand that trainers are busy and might not see messages or voicemails immediately. Be polite and friendly when you reach out, and understanding if people don’t reply immediately.

Finally, don’t be disappointed if the trainer doesn’t reply or says the horse isn’t for sale or is already spoken for. There’s a constant flow of racehorses retiring from the track, some of which are available and some that aren’t.

Information: A Two-Way Street

Once you connect with the trainer, he or she might put you in contact with the horse’s owner or they might handle correspondence and a potential sale themselves. Regardless, be prepared to give as much information as you’re hoping to receive.

“Explain who you are and what your intentions are, that when the horse is finished with their career, you’d love to give them a home away from the racetrack,” Napravnik says. “Just be straightforward.”

Trainers (and owners) typically want to see their horses end up in good homes after their racing careers, she says, so supplying references can help them feel confident about sending the horse home with you: “Say, ‘Here’s the trainer I work with. Here’s my vet. Here’s my farrier. They can tell you I pay my bills and I take good care of my horses.’ ”

Finally, remember that social media can be a useful tool for trainers and owners, as well. “If some random person called me up and said, ‘Hey, you’re running this horse, I’d really love to give them a home,’ the first thing I do is check their Facebook profile or find them on another social media platform,” says Napravnik. “Does this person have pictures on their social media that correlate to what they told me?”

If the trainer responds and continues the conversation, get as much information about the horse as possible.

“I usually ask about vices and injuries, as well as if the horse has any problems with breathing (i.e., if he makes noise while galloping or flips his palate),” Ruberto says. “I want to know if the horse has good work ethic or if it goes out to train and tries to buck the exercise rider off. I check the horse’s race record on Equibase to see if there are any long breaks that are not consistent with track meets ending or southern/northern moves and ask the trainer about them, if they are out of character for the horse.”

Napravnik agrees: “Ask the trainer what their temperament is. How are they to handle in the barn? Ask them how long they’ve had the horse, if he’s had any problems in that time.”

Another question that could provide you with useful information if you purchase the horse is whether he gets regular turnout.

“If the horse is fortunate enough to live at, say, Fair Hill, they might go out in a small paddock or round pen every day,” Napravnik says. “If they live at Pimlico? That’s typically not happening. Does this horse ever get a break and go to the farm? If you know that information, you can be better prepared for when you bring the horse home,” and can plan the horse’s management transition accordingly.

Many times buyers purchase horses straight off the track sight-unseen. If the conversation is going well and you’re close to the horse’s home track, you can ask to visit, check him out or even have a veterinary prepurchase exam done. Some trainers are open to this, while others aren’t. Have an honest discussion, and try to land on a solution everyone’s comfortable with.

A word of caution: As with any segment of the horse world, you might get varying degrees of honesty in the answers to your questions. Keep a buyer-beware mentality, and trust your gut about whether a seller is being transparent.

However, Napravnik says, “most of the time trainers want the horses to go to a good home,” and, so, will share as much information as they can.

Finally, remember that trainers might only have had the horse in their care for a short time (sometimes you can see the trainer/owner change in races or works on sites like Equibase). In these cases appreciate what the trainer can offer and understand if they genuinely don’t know an answer. Veterinary records don’t always move with racehorses.

Decisions, Decisions

You’ve connected with the trainer, shared information, asked questions and, much to your delight, the trainer says you can bring the horse home (either now or when his career ends). Before you hook up the trailer, remember a few important tips:

■ Recognize the match might only be good on paper. Regardless of how much you wanted a horse when you saw him at the track, you’re not obligated to take the horse if — after you’ve taken a closer look — he doesn’t suit your needs.

■ Be honest with yourself about your requirements. Not every rider needs the unicorn who comes off the track with no injuries or breathing issues and the athletic ability to clear the moon or produce a 10 piaffe. If you have legitimate upper-level goals, you might have to pass on a horse with potentially limiting issues. But, Ruberto says, “be realistic in your own ability and goals. If you want the horse to hunter pace or to do lower-level dressage, don’t run away because the horse has an old, healed injury that has no bearing on your goals.”

■ Remember you’re dealing with a live animal. Don’t forget that horses can end up with new injuries in a single moment. “Anything can happen,” Napravnik says. “It could be perfectly fine today and lame tomorrow. You have to go in hoping for the best but willing to accept that risk.”

■ Don’t take the horse unless you can support him indefinitely. Not everyone can collect pasture puffs so your decision to buy or walk away might come down to whether you can afford the horse. It’s OK — responsible, actually — to decline to take a horse on financial grounds. “It’s always better to spend ‘extra’ money than the money you use to pay the mortgage,” Napravnik says.

■ Have a support system — and use it. “The most important thing to do when looking at a horse is to consult with and bring someone along that is knowledgeable about picking out a nice horse,” Ruberto says, especially if it’s your first horse straight from the track.

If you’re not sure whether a horse is a good purchase, if a particular injury will impact a career or whether a horse’s price is fair, ask your network.

The End Game

If, ultimately, you decide a horse you’ve been lusting after isn’t right for your situation, that’s OK. Tell the trainer — don’t leave them hanging — and thank them for their time, input and honesty. If you decide to move forward, however, it’s time to discuss price.

“Don’t expect a free horse,” Ruberto says. “By the time a horse retires from the track it has had thousands spent on it to get to that point.”

When discussing price, be respectful, she adds. “Trainers know the market is hot and horses are much more in demand than they used to be. You can make an offer, but don’t low-ball the trainer and then act like you’re doing them a favor. That just makes the trainer and owner feel like you think their horse has no value. Many of these connections really care for their horses. The quickest way to not be invited back is by acting like you know more than you do or they do.”

If you reach an agreement, get it in writing. Sign a contract or a bill of sale (download one at therrp.org/bill-of-sale) to protect both parties and establish ownership of the horse.

Full Circle

Going from admirer to owner doesn’t have to be a complicated process if you’re prepared for what lies ahead.

“Educate yourself,” Ruberto says. “Don’t waste anyone else’s time. Be polite — you’d be surprised how many people are not. Come prepared but ask questions. Talk to people who have the experience to lead you in the right direction when it comes to purchasing a horse off the track.”

Above all, remember the trainer you approach has likely invested a lot of time, energy and money in the horse you’re coveting. Many are elated to assume the admirer position for their former charge’s second career.

“I’ve spoken to a lot of trainers at the track that were thrilled to hear that someone had been following their horse’s career,” Ruberto says. “The majority of trainers I buy from love to see updates on their former horses. Please do reach back out. Send pictures with those updates. We love them.”

Erica Larson works in marketing and communications for the nation’s oldest and largest racehorse adoption program. She resides near Lexington, Kentucky, with her two off-track Thoroughbreds.

The Claiming Game

There’s another way to secure a horse you’ve been following, but it can be more complicated and impossible in some scenarios. It’s the claiming race.

“Any horse entered in a claiming race is essentially for sale,” says Jen Ruberto, who runs Wire to Wire Sporthorses, in Lisbon, Ohio. She says claiming races basically level the playing field: A trainer can’t drop a horse down a class to compete against horses with less ability without risking that horse being claimed (i.e., bought) by another stable.

Strict rules regulate who can claim horses. “To claim a horse, you need to be a licensed owner at that track, have claiming money (plus whatever taxes apply) in your account and have a licensed trainer willing to claim for you,” Ruberto says. “Without those things in line, you cannot claim a horse.”

If you’re eligible, you and/or the trainer fills out a claim slip to secure the horse. But even this isn’t without fail, Ruberto says. “Any mistakes on the slip, even on the date, will void the claim,” she says, which means no sale.

While it’s not for everyone, claiming can be a quick way to purchase a horse if you have the proper arrangements in place.