Champion Beholder won three Breeders’ Cup races, including one as a 2-year-old, during her long and illustrious career. Courtesy Breeders’ Cup/Thom Shelby

Seabiscuit, the popular runner in the 1930s who became the subject of a bestselling book in 1999 and a major movie in 2003, raced 35 times as a 2-year-old. That didn’t stop him from competing a total of 89 times over six years. In fact, Seabiscuit’s rigorous 2-year-old season might have helped him stay sound.

Racing 2-year-olds is sometimes viewed as rushing young horses that aren’t yet physically mature. Some people, both in racing and in other disciplines, believe horses shouldn’t compete until they’re older.

Scientific research, however, tells us exactly the opposite. Horses generally develop stronger and stay sounder if they begin training and racing at 2, provided trainers tailor schedules appropriately for each individual.

Building Strong Bone

The key to a sound horse starts with his skeletal development. Kathryn Dern, DVM, MS, Dipl. ACVS, a surgeon at Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, explains how this process works.

“Bone is a dynamic tissue,” Dern says. “In spite of the fact that we think of bone as being very hard, it flexes and bends in response to loads, activating the cells within to adapt the shape and density of the bone to better deal with the stress of exercise.”

This is crucial from the very beginning of a horse’s life, which is why Dern and many other veterinarians emphasize the importance of turnout for foals and yearlings. The exercise young horses get from turnout helps them develop. Then, once a horse learns its early lessons and is ready to begin training, the bones respond even more specifically to that training. The bone remodels because of the exercise, Dern explains.

“The term bone ‘modeling’ refers specifically to the change in mass or shape of the bone,” she says. “This is best recognized in the racehorse by the adaption of the metacarpus (cannon bone of the front limb) during exercise. It triples in size in response to exercise from where it starts as a yearling to what is required in the racing athlete.”

Dern explains that bone remodels through the coordination of cells that both resorb and build new bone. Horses “are trying to create the most efficient skeleton possible,” she says.

Studies show that this process occurs during much of the horse’s 2-year-old year. In one study researchers compared Thoroughbreds and Standardbreds (harness racehorses) that entered training at age 2 versus those entering training later. The horses that competed at 2 had more total race starts and greater earnings than those entering training later.

“It is also important to know that bone trains to the level of training experienced, not to the amount of training each day,” Dern says. “Hearts, lungs and muscles respond to the amount of work. This difference makes a trainer’s job a balancing act, especially early in the horse’s career.”

Training the Individual

The trainers who succeed with 2-year-olds and then take those horses on to multiple years of racing know how to maintain that balancing act successfully. Richard Mandella is a Hall of Fame trainer based in Southern California who has won nine Breeders’ Cup races, four of them with 2-year-olds.

One of Mandella’s best horses, Beholder, won three Breeders’ Cup races, including one as a 2-year-old. She raced through age 6, won four championship titles and earned more than $6 million.

“You have to treat them individually,” says Mandella. “Beholder trained well at 2, though she carried a lot of weight. The first time I ran her she was still pretty fat and soft, and she showed it in her race (finishing fourth). But out of it, the race just turned her around, and she was a racehorse from then on.”

Mandella is a master at knowing when to give horses a rest. He often gave Beholder time off, which he believes contributed to her long and successful career. She is now a broodmare in Kentucky.

Some horses are built to run better as 2-year-olds, Mandella points out, while others need more time. Another horse he trained, Phone Chatter, a Breeders’ Cup winner and 1993 Champion 2-year-old, had her best season at 2. She competed for three more seasons, winning only one more race.

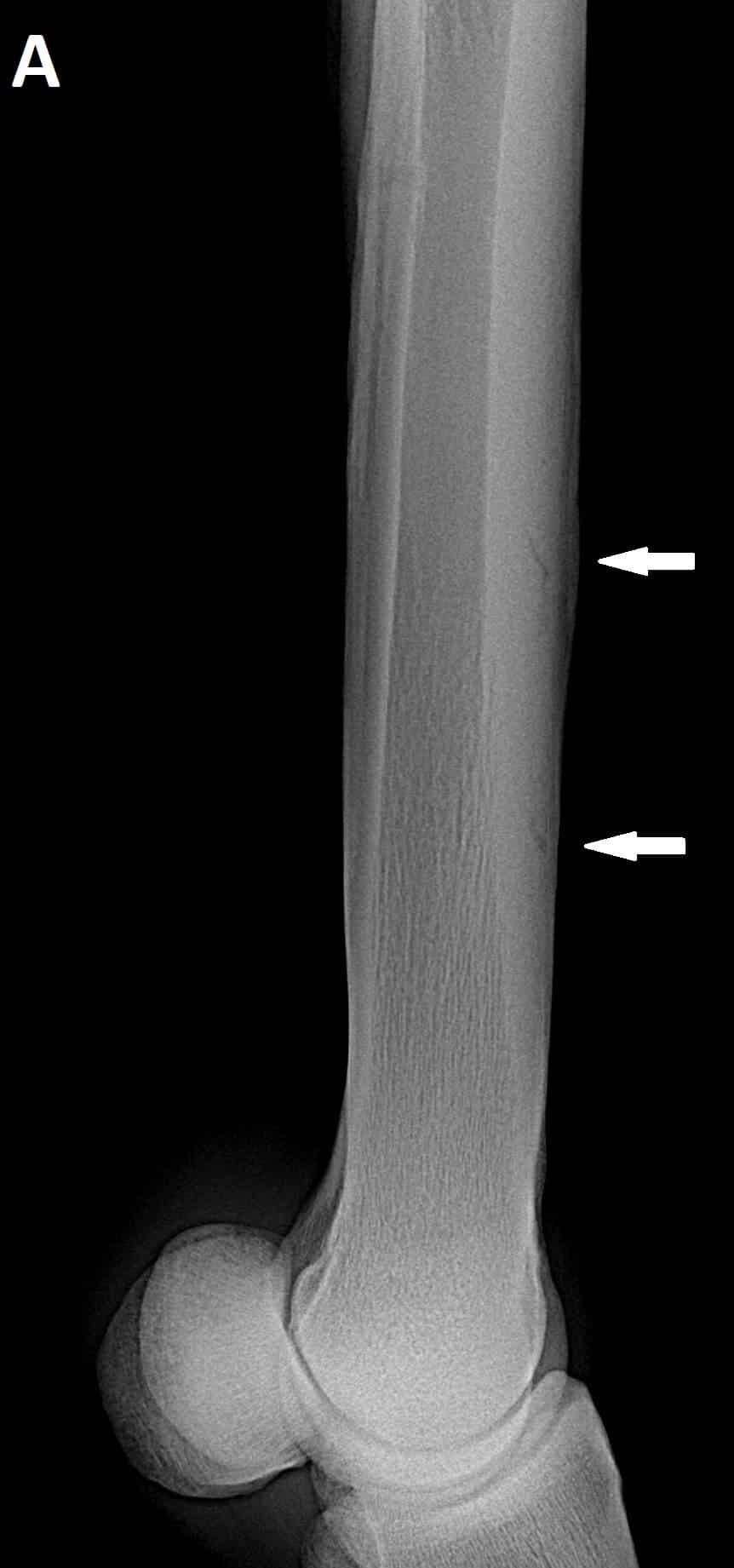

Indeed, the shin or front of the forelimb cannon bone illustrates the way bone responds to exercise. As the horse trains, the shin remodels to increase the thickness and density of the cortex (the outer part of the bone), Dern says.

“In a perfect world this bone modeling/remodeling occurs faster than the damage accumulated from the stress of training,” she says.

Racetrack veterinarians and trainers work together to diagnose stress fractures, which can occur when the remodeling doesn’t keep up. They can modify the training schedule appropriately or, if necessary, perform surgery to repair the damage.

These stress fractures are often called bucked shins. Trainers check a young horse’s shins daily, looking for heat, swelling and any other signs of injury or discomfort.

“It can be just a little tender,” says Mandella. “Some buck out with an actual periostitis (inflammation of the membrane that covers the bone) reaction, and some never have it.”

As a young man Mandella started and rode long yearlings and 2-year-olds on a California farm. He experienced a wide range of horses’ reactions to early training.

“Some of them would get sore shins just galloping,” he said. “That tells you they’re not made to go early.”

Others thrive on it. Mandella recalled a horse he trained in the 1970s named Bad ’n Big, who never had a shin problem. Bad ’n Big raced five times as a 2-year-old and competed until his 7-year-old season, earning $593,575.

Bucked Shins Treatment X-Ray

Photo Courtesy Dr. Ryan Carpenter

The Right Time to Train

What about letting a horse just be a horse for the first few years of his life? Would it be better to let future racehorses grow up moving around on pasture rather than putting them into training?

Actually, no. First of all, many horses simply prefer to stand in the sun eating grass than run around. But, perhaps more importantly, encouraging bone to remodel to the type of exercise a horse will be doing in his job can give animals the structural tools needed to perform at their best.

“ ‘Being a horse’ is very important to the developing horse, from birth to about 18 months of age,” says Dern. “Early play and exercise essentially prime the musculoskeletal system. Examination of the cartilage in the fetlocks of foals kept on stall rest versus foals out in a pasture revealed that the cartilage in the pastured and exercised foals actually changed in both structure and composition. These changes were still detectable when the horses went into training.”

Traditionally, a popular method of determining when a young Thoroughbred was ready for training involved radiographing the knees to see if they were open (growth plates have not finished solidifying and, so, are not ready) or closed (with the bone having matured enough for training).

“A better place to monitor is the lower joint of the horse’s knee,” says Dern. “It is actually the middle carpal joint, but the lowest joint does not flex so the middle joint is better known as the lower joint of the knee. That is the site — specifically the radial carpal bone on the inside aspect of the lower joint — where a horse is most likely to get into trouble and suffer an injury that can affect the rest of the horse’s career. If that bone is training well, most of the rest of the horse is training well.”

So when exactly should a young Thoroughbred begin race training?

“The research clearly tells us that it is best to start training while the bone biology is still primed to build and rebuild the skeleton so that it can withstand the rigors of training in adulthood,” says Dern. “When a horse is growing, he has a cell population and associated blood supply to the bone that is present until the end of growth. Once the horse is mature (about 20 months in a filly and 22 months in a colt), this cell and blood supply begins to atrophy because it is no longer needed for growth. Eventually it disappears.”

If horses begin training before the cells and blood supply have atrophied, they have a better chance of building that efficient skeleton. The time spent remodeling the bone then more likely results in longer, sounder racing careers, as well as productive second careers.

Trainers and veterinarians can apply what’s been learned from this scientific research, using good training methods and monitoring horses constantly for potential problems.

“The most important single quality in a good trainer is the ability to recognize when a horse is no longer happy,” says Dern. “Many horses love to train and are happy doing it. Once they begin to lose enthusiasm for training, something is going wrong. You need to find the reason.”