What happens when a future racehorse is offered at public auction

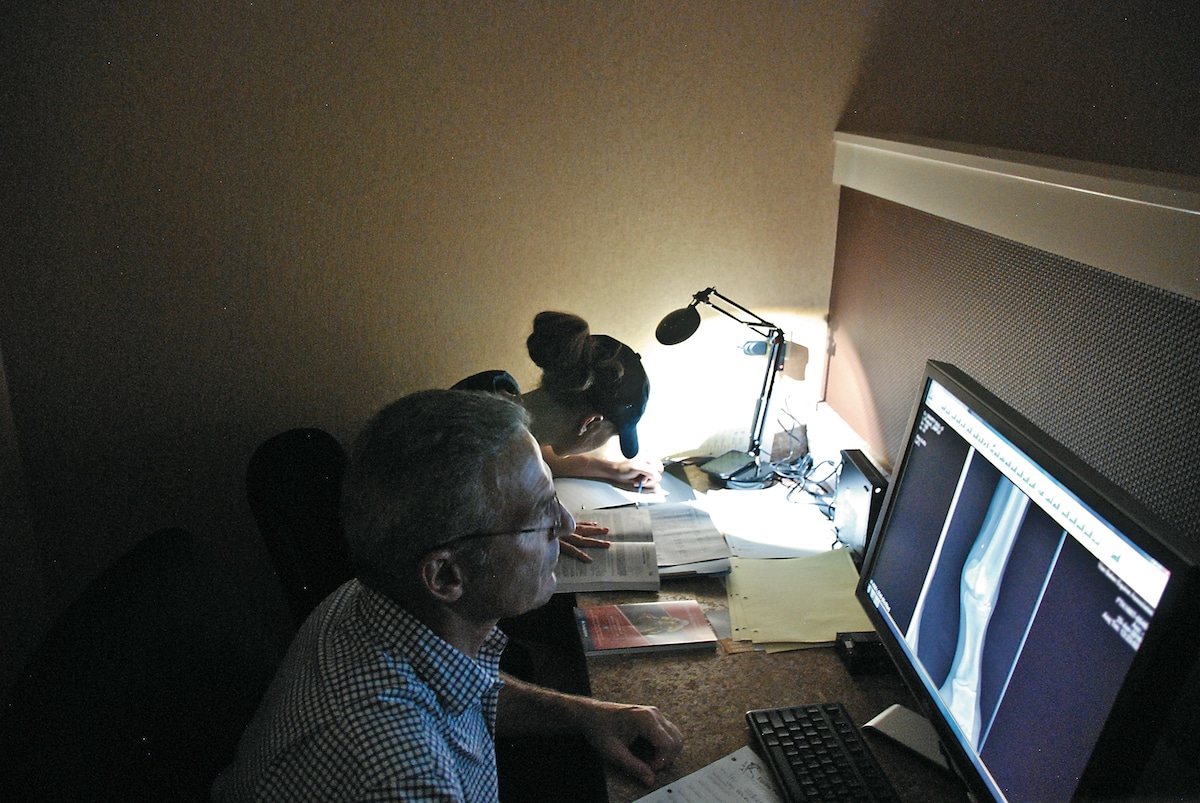

Agents and veterinarians can view horses’ medical records on file at the sales company’s repository. Courtesy Alexandra Beckstett

Thousands of Thoroughbred yearlings go through the Keeneland sale ring each September. Your off-track Thoroughbred could have been one of them, or perhaps he sold as a yearling at another auction, or as a weanling or a 2-year-old.

Thoroughbred public sales around the country give people an opportunity to buy horses at almost any stage of their careers. Prices range from the incredibly affordable to the multimillion-dollar stratosphere.

“Most of the show hunters I deal with on a regular basis are private sales,” says Thoroughbred breeder and seller Carrie Brogden. “The Thoroughbred market is the opposite — 95% of the sales of the weanlings and yearlings are through the public auctions. To me it’s by far the best way to have your horse appraised and seen by the right buyers.”

Brogden, who sits on the board of the Retired Racehorse Project, operates the 530-acre Machmer Hall in Paris, Kentucky, with her husband, Craig, and her mother, Dr. Sandy Fubini, a veterinarian. Each year they sell at many sales throughout the country, often at yearling auctions. Machmer Hall has bred such notable horses as two-time champion Tepin, who won the 2015 Breeders’ Cup Mile.

Part of a seller’s job is to evaluate horses to determine which sales would be best for them. Most racehorses that sell at auction are weanlings, yearlings or unraced 2-year-olds. Because each step up in age requires more training, feeding and development, buyers expect to pay the least for weanlings, more for yearlings and even more for 2-year-olds.

Keeneland, Fasig-Tipton and the Ocala Breeders Sales’ (OBS) Company are three of the largest national auction houses in the United States. Keeneland and Fasig-Tipton are based in Lexington, Kentucky, while OBS is based in Florida. All of Keeneland’s sales are conducted at the company’s home base of Keeneland Race Course, and OBS holds its sales at its Ocala complex. Fasig-Tipton holds sales in Kentucky, upstate New York at Saratoga Race Course and other states such as California, Florida and Maryland.

Selecting a Market

The weanling market typically starts in the fall and spills over into the following January. Brogden explains that even though horses might technically sell as yearlings in January, they are considered “short” or young yearlings, and buyers and sellers view them more as weanlings.

“The first really significant yearling sale would always be the July select sale (at Fasig-Tipton),” Brogden says. “That tends to be for horses that are very precocious, with good vetting physicals, nice walks and pretty uncomplicated front ends. You may not have the most fashionable pedigrees, but you can certainly get an athlete at that sale.”

Many of the best prospects sell at the Fasig-Tipton select yearling sale at Saratoga in August and in the first part of the massive Keeneland September yearling sale. The top-priced horse at Saratoga in 2019 sold for $1.5 million, while at Keeneland last year the top price was $8.2 million.

While some racehorse owners look for weanlings, yearlings and 2-year-olds, many zero in on a particular type for reasons that mesh well with their business plan. Some people prefer to buy 2-year-olds so they can race the horses shortly thereafter. Those who buy yearlings realize they must hold onto the horse for another year before it can race, but the owners or their trainers might prefer more control over the breaking and early training process.

Choosing the right market is an art form in itself. Typically, sellers choose either a national marketplace or a regional one. The national market brings buyers from all over the world and could result in higher prices. However, a lesser horse might get lost in the crowd and might do better in a regional sale. If a horse’s sire appeals to a particular region, that might be the best place to sell that animal.

The Price of a Racehorse

Theoretically, the closer a horse gets to being able to start in a race, the more he costs. However, that can backfire for a seller if the horse doesn’t develop into a talented racehorse. Many horses with expensive pedigrees fail to fetch big prices at 2-year-old sales if they aren’t very fast.

When it works, the chronology of sales can pay off at every stage. For example, Nyquist, winner of the 2016 Kentucky Derby, first sold as a weanling at Keeneland for $180,000. Ten months later as a yearling at Keeneland, he brought $230,000. And at a Fasig-Tipton sale of 2-year-olds in Florida, he sold for $400,000. Nyquist went on to earn $5,189,200 and today stands at stud in Kentucky for $40,000 per foal.

Brogden and her family sold Tepin for $140,000 as a yearling, and later as a broodmare Tepin sold for $8 million. Brogden also recalls Mind Your Biscuits, a horse no one seemed to want at several sales.

“We bought him as a short yearling for $47,000,” says Brogden. “We took him to the yearling sale and didn’t get him sold. We took him to the 2-year-old sale. Everyone thought he was too slow.”

Mind Your Biscuits again didn’t sell, and Machmer’s partners bought them out. The horse certainly wasn’t slow because he went on to earn $4,279,566.

From Prep to Purchase

Just what does a horse do at a sale? Sellers prep horses appropriately at the farm or training center (see the Fall 2016 article in this series), getting them fit and working on their ground manners, and then ship to the sale grounds in time for the sale.

For weanlings and yearlings, that might be a few days before the actual sale. The Keeneland yearling sale, for example, encompasses so many horses over a two-week span that horses arrive in stages, the ones in the early part of the sale leaving before the last ones come in.

Horses usually remain at the sale grounds longer for 2-year-old sales. That’s because these sales include the chance for prospective buyers to see the horses train under saddle on the racetrack. Sales companies usually schedule a preview a couple of days before the sale, where every horse must gallop or work at speed over the track.

All sale horses are available for inspection at the sales barns in the days leading up to the sale. Prospective buyers or their agents put together a “short list” of horses they might want to buy and then ask the sellers to bring each horse out.

“The horses ship in the day before they start showing,” says Brogden. “They all get baths, and those that need it get their ears, faces and pasterns trimmed and their manes pulled.”

When anyone comes by wanting to see a horse, one of Brogden’s employees brings it out in a halter using either a chifney or a shank. Buyers usually want to see the horse standing square and walking back and forth in a straight line so they can evaluate conformation.

“It’s astonishing how quickly the horses learn,” says Brogden. “Thoroughbreds do very well in repetitive events. Once they figure out, ‘I walk here, I turn this way, I walk back, and I stand up,’ it is really surprising to me how quickly they pick it up.”

The process can be tiring, however, especially for popular horses. Brogden says her record for showing one horse was 132 times a day, but on average for a busy sale it can be 50 times a day.

“We take them for water breaks, as well,” she said. “But that’s why they have to be so fit, so they can handle being shown to that many buyers.”

Each sale has its own warranties, many relating to soundness and wind (airway issues). Depending on the specific conditions of sale, prospective buyers might request that their veterinarians conduct various soundness exams, not unlike a prepurchase exam in the sport horse world.

It is difficult to ask a young horse to undergo multiple exams, however, especially X-rays of limbs or endoscopic exams of the airways. Therefore, sales companies have developed repository systems, where sellers have exams on file that prospective buyers, their agents or their veterinarians can peruse.

“It’s a lot safer,” says Brogden, who explains that veterinarians can look at the files in the repository instead of having to do the exams themselves. She adds that videoscopes, which are videos of endoscopic airway exams, are becoming very popular.

After the sale, the new owner makes arrangements to ship the horse to the next stage of its life. With weanlings and yearlings, that could mean more turnout time to continue growing. Yearlings might soon undergo initial breaking and training. As for 2-year-olds, depending on the individual, they could go straight to the racetrack to prepare for their racing career.