What do those jargony race records really mean?

Lava Man climbed the racing levels from $50,000 claimer to $5 million-earning stakes winner before retiring to be a pony in trainer Doug O’Neill’s stable. Courtesy Flickr/ Maryland GovPics

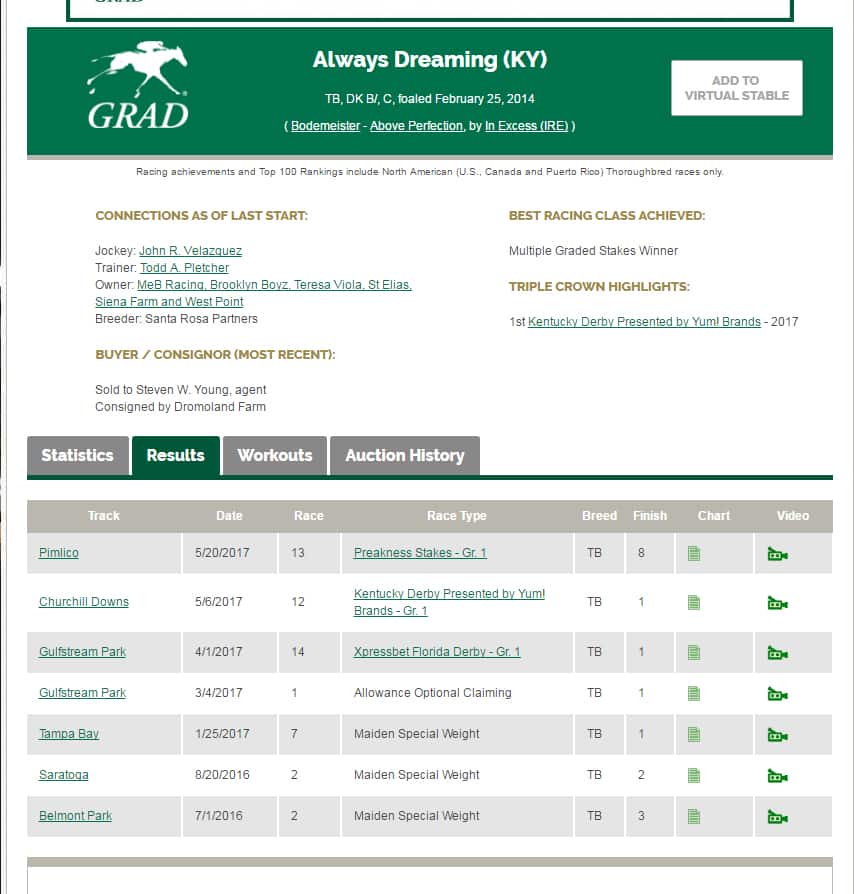

Anyone with an off-track Thoroughbred at some point wonders: What did my horse do on the racetrack? If you find your horse’s racing record, you might see jargon such as “claiming,” “allowance, and “maiden” races. What does this mean?

These terms describe the level at which your horse performed. Initially, they might look like gibberish, especially when you examine a full chart and see one race for horses “which have never won $10,000 once other than maiden or claiming” and another for horses “which have started for a claiming price of $40,000 or less.”

But there’s a method to the madness. Races are categorized so that, theoretically, every horse entered has a chance to win. It’s not too different from a horse show, where jumping classes are defined by the height of the fence and reining classes range from novice to open. Whereas some show classes are categorized by the rider’s age or experience, in racing the category always revolves around the horse.

“It’s sort of like a grade school system — you’re learning a little bit more in each grade,” says trainer Mike Stidham. “It enables the younger, inexperienced horses to not have to run against the older, more experienced horses. It lets them climb the ladder.”

A trainer for 37 years, Stidham has a large national stable of horses. He is based in Louisiana in the winter and Chicago and Delaware during the summer. He has horses of all classes, from low-level claimers to graded stakes runners and youngsters to war horses.

Defining the Ranks

The primary race categories are stakes, allowance, claiming and maiden. Stakes such as the Kentucky Derby are the highest-quality and biggest-paying races, and nearly every track has its version of these. Allowance is the next level down, and claiming is the lowest level. Maiden races are for horses that haven’t won yet.

Horses running in allowance races have broken their maiden, but they’re not necessarily ready yet to run against stakes horses. In these races horses might receive allowances based on experience, age or how recently they ran. These are often tied to how much weight the horse is assigned. If a horse hasn’t won as many races as his competition, he might be “allowed,” say, 3 pounds, getting to carry less weight than the other horses.

Often, these races have other “conditions,” or sublevels within the category. An allowance race might be restricted to horses that haven’t won a certain type or number of races, haven’t raced since a particular date or haven’t won a race worth a specified level of money.

In a claiming race, a horse can actually be claimed away from its owner for a certain price. Authorized owners can “put in a claim” for a horse at the listed price before the race is run. The original owner gets whatever money the horse earns in the race, plus the claiming price, and the new owner gets the horse, no matter how it performs.

The idea is to enter a horse in as low a level as possible to win the race, but not have him claimed. Take, for example, a $40,000 claiming race. If a horse worth $10,000 is entered, chances are he won’t run well enough to earn any money, and no one will buy him. If a horse is worth $100,000, he could very well win, but the owner will likely lose him to a claim and only receive 40% of what the horse is worth on top of the winnings.

If all the horses are worth $40,000, the race should be very competitive, and an owner could do quite well. In a $55,000 race at Aqueduct in New York in April 2017, Mt. Brilliant Farm’s filly Desert Duchess won, earning $33,000, and was claimed for $40,000.

Choosing One’s Spot

A trainer must find the best level for each horse at every point in its career, which is not always an easy task. Even that first race can be tricky, because maiden races come in “straight” or “open” (i.e., special weight) events, where a horse cannot be claimed, as well as various claiming levels.

When Stidham trains a horse, he analyzes where that horse belongs based on several factors.

“We’re lucky enough to have a lot of horses in the barn that we have a line on because they have previously raced,” says Stidham. “We are able to work them with the new horses that are coming along to get a line on the new horses and see what their approximate level should be.”

In consultation with the horse’s owner, Stidham determines what level to first attempt. He also considers other aspects, such as whether the horse might prefer shorter or longer distances and dirt vs. turf.

“Their breeding plays a part in it, what the sire and dam did as racehorses,” Stidham says. “It’s a big puzzle, and you try to use as many pieces as you can to learn about the young horse.”

An auction price might also help. If a horse cost $50,000 as a 2-year-old in training, an owner isn’t going to want to risk the animal in a $10,000 claiming race.

Ideally, a horse begins at one level and improves so the trainer can run him in better races and win more money. That’s another crucial reason for finding the right level early, because horses usually gain confidence as they do well.

“If a horse continues to run over his ability level, you risk them not wanting to try as hard,” says Stidham. Conversely, the horse could try too hard and injure himself.

Claiming races provide many opportunities. Trainers who are good at what is called “the claiming game” delight in claiming horses for very little money and moving them up the ladder.

Lava Man, now a stable pony in the barn of trainer Doug O’Neill, who won the Kentucky Derby with I’ll Have Another as well as Nyquist, proved how lucrative claiming can be. Owners Jason Wood and Steve, Dave and Tracy Kenly claimed Lava Man for $50,000 in 2004. Under O’Neill’s training, Lava Man went on to earn $5,180,678 — more than any former claimer in history.

Reaching the Bottom

Horses might move up or down the levels throughout their racing careers. A prolonged drop in level often indicates a horse is coming to the end of his career. Responsible owners and trainers then start planning that horse’s second career. Colts and fillies often retire to the breeding shed, while geldings are prime candidates for riding or show horses.

Stidham and one of his clients, Arthur Hancock III, recently retired 10-year-old gelding Trend, an earner of $388,662.

“He was a multiple stakes winner,” says Stidham. “We had dropped him in for $50,000 (claiming) and then $40,000. He was running well for $40,000, but he needed another drop. Arthur decided to retire the horse. We’re making a racetrack pony out of him.”

Many horses Stidham trained have gone on to successful second careers. At age 18 Sandburr, an earner of $476,321, is now living out his retirement on a farm in Texas.

“We get pictures of him out in a pasture enjoying his life,” Stidham says.

The levels of races can also expose horses that either don’t want to be racehorses or don’t have that particular ability.

“A lot of times these are horses that are just too slow,” says Stidham. “They’re sound and kind, good-looking horses that wind up having really good careers as hunter/jumpers, dressage horses and that type of thing.”

Take-Aways

While racing ability might or might not correlate to how well a horse does in a second career, it’s always fun to discover what your horse did before you got him. And if he happened to win a race, chances are the racetrack photographer could provide you with a photo of that victory — be it in a maiden or a stakes — to hang in your tack room.