Besides being bred to race, all off-track Thoroughbreds in their second careers have something in common: Core strength is critical to their soundness, no matter the riding discipline.

But when horses are as athletic, willing and eager as many OTTBs are to get to work, it can be tempting to skip ahead, progressing through levels without putting in the effort that will help them train optimally and even resist injuries. This applies as much to veteran OTTB sport horses coming back after an injury or extended vacation as it does to recently retired racers.

We spoke with a veterinarian who specializes in sports medicine and with two trainers who emphasize strong cores and correct biomechanics in their methods about what you need to know to build strength and agility and, thus, versatility in your OTTB, while supporting soundness.

This article is a continuation of a series that began with groundwork. Catch up on the groundwork segment here!

Core Strengthening Under Saddle

Sharon Vander Ziel, a longtime dressage trainer and a senior education coordinator at the United States Dressage Federation, also in Lexington, regularly teaches riders who have OTTBs and once trained her own to Prix St. George.

“He had some soundness issues all through his life,” she says. “But if he used his core and his topline, then he would move more evenly and correctly.

“In general, for dressage, OTTBs need to learn to use their core/abdominal muscles in a different way,” she says. “Most Thoroughbreds are eager to go forward so generally need to learn more about going in a relaxed and consistent tempo. I feel if you develop the muscles correctly and help the horse build a topline, they (can do this), stay sounder longer and are happier in their work overall. They also develop the muscle to do more advanced work with less overall stress.”

She believes it takes about a year to truly develop a good topline.

“Dressage makes that easy,” she says. “You can follow the progression of the dressage tests and Pyramid of Training/Training scale. This gives you a training plan to develop the muscles and rideability, starting with developing relaxation and correct alignment through circles and bending lines. This also helps start to develop the core and abdominal muscles.”

She says most OTTBs need to learn to use their body correctly, following their nose around turns with the shoulders, middle and hind end flowing behind them, aligned, which is something you can monitor from the saddle.

“I think the easiest thing I’ve found for riders is to look at the poll,” she says. “If they’re going around a curve, the base of the outside ear should be slightly in front of the base of the inside ear. A lot of times what you’ll see when the horse is coming into dressage from racing or a different discipline is that their head is actually turned a little bit to the outside, and maybe the base of the inside ear is a little bit leading. When that happens, a lot of times they start the turn with the inside shoulder … (and) they’re going to be landing harder on that front leg.”

Also, if the horse’s spine isn’t aligned properly as he moves, she explains, he’ll compress certain vertebral areas more than others, impeding how he uses himself in the turns.

“By aligning them correctly, they’re going to be able to balance the weight on all four legs more evenly,” says Vander Ziel. “This becomes very important when dealing with a horse with old injuries. The more balanced they work on all four legs and build correct muscles, just like humans, the more likely they are to stay sound.”

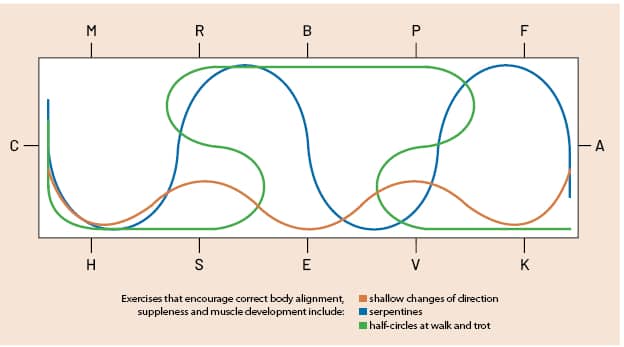

To achieve this alignment and teach OTTBs to be supple in their bodies, she uses shallow changes of direction, serpentines and half-circles at the walk and trot during every arena ride — exercises that become part of the warmup. Schooling transitions between gaits is also very helpful, she adds, if you keep the horse’s level of training in mind.

“I think that the transitions only really build the muscles correctly when they’re done correctly,” Vander Ziel explains. “Say if you do a transition from the trot to the walk or the walk to the trot, and the horse throws his head up. That would show he’s not using his core correctly, and that isn’t going to develop the correct muscles. However, if you try to force him into the situation and he doesn’t really have the training or the muscling to do it, and you’re trying to do it over and over and over again, you may cause more harm.”

Also keep in mind that too many transitions can wind Thoroughbreds up, making them more nervous. Pay attention to the horse’s mental state and allow him time to relax.

Here are some other exercises Vander Ziel recommends:

■ Transitions within the gait, mostly at trot in the beginning. “Focus more on the slowing; Thoroughbreds know how to go. If you want to build the horse’s muscles, every other day for this one.”

■ Spiral in and out on a circle, which helps the horse learn how to move off the inside leg without getting stiff. This can be done for five to 10 minutes every ride in the arena.

■ Train them to do turn on forehand correctly. “This is a piece I see missing in so many horses. My goal is the horse learns to move his left hind leg a little under himself when you use your left lower leg (the same to the right) … without pulling the horse around with the inside indirect rein. This should be done every ride until they have mastered it.”

As you work, watch for signals the horse might need to take a break, such as tail-swishing, getting more active in the mouth, stopping, running out of the exercise or other evasions or signs of frustration — basically, anything that shows up after the horse has worked nicely for 10 or so minutes or more, says Vander Ziel.

“Sometimes it’s not that the work is wrong,” she explains, “it’s just that it’s difficult for them to maintain it for a long period of time. People need to know their horse, and if they start acting differently, then I think they need to trust the horse. Think of a way to back off the exercise, making it into something a little bit easier, and then work back up.”

Courtesy The Horse staff

Core Strength Dividends

Aside from helping the horse work in a biomechanically correct way and overcome existing injuries, building core strength helps prevent injury. Both Vander Ziel and Musgrave are proponents of working horses on different surfaces, both in-hand and ridden, and varying terrain to build soundness and agility.

“Most horses are injured when they encounter something that they didn’t train for,” says Musgrave, giving a pasture injury as a classic example. “So maybe they didn’t train to step in a hole, and so their leg stabilizing muscles weren’t prepared for that. But if we can figure out ways that we can use nature to teach them to self-organize and self-balance and self-coordinate,” it will prepare them for moments when they aren’t on manicured, flat surfaces, whether during rides or turnout.

Musgrave also likes to promote play in her horses, teaching them to chase objects such as yoga balls or pool noodles. “I can get movement out of my horses that I would never get just trying to push them in a circle. When you combine the play drive with movement you can get some pretty spectacular things.

“I think a lot of times we are so cautious about allowing our horses to explore things and explore movement because we’re afraid that they’re going to get injured, when in reality if they’re only ever on a very flat, curated surface, the moment they come into a not flat and not curated world, they are really at risk because they don’t know how to deal with that.”

Latif has observed that, trained or not, some OTTBs sustain core strength and sidestep injury better than others.

“Most of the time they don’t have a conformational but, rather, a constitutional quality: strong and tight connective tissue that keeps the trunk from giving in to gravity by a tight shoulder girdle sling, even if the muscular part is not perfectly trained,” says Latif. “These horses are maybe not the ones with huge, expressive movements, but they will be able to keep healthy much easier.”

Also, don’t discount the impact of good husbandry and stewardship of the horse’s health.

“From my experience, gastrointestinal and mental health are important prerequisites to help those horses into their new function,” she says, “and sometimes the successful mental transition to a less intense management program, with more pasture and social contacts, requires more time and smaller steps than the transition to another physical demand.”

Be Mindful of Previous Injuries

While building core strength in the OTTB, it’s crucial to keep in mind any existing injuries.

For example, if a horse has had issues with his hocks, Vander Ziel says to work on level surfaces as much as possible until he can strengthen his core, get his hocks beneath him and engage.

If a horse has coffin bone pathology or front ankle issues, he needs to engage his hind end to get weight off the forelimbs.

Finally, if the horse has arthritis of the spine or neck, it’s important to work him so he’s stretching the back (rounding, not bending) and, thus, spreading out the vertebrae. Be sure he’s not working in such a way — head up, back tight — that compresses the vertebrae.

Take-Home Message

Your retired racehorse’s core has been trained before and can be trained again to perform his second career job optimally. Never rush, and always look for signs it’s time to pause or to scale up the work. Most importantly, consult your veterinarian about any former injuries or physical limitations your horse might have, and relay that information to your trainer or instructor before beginning your core work in earnest.