Your Story: Schmoopy Is As Schmoopy Does

June 27, 2014From Malinda:

Very few people know Schmoopy’s real name. At the barn they call him “MG” and I refer to him as “Pony Face” and address him as “Schmoopy”. His Jockey Club name is “Move the Gold”, a nod to his mildly-famous forebearers, Count Prospector (a son of the ubiquitous Mr. Prospector) and Conveyance (a mare by Empery and out of Message Received by Hoist the Flag). Schmoopy was bred in New York by Stephen DiMauro and foaled in Saratoga on March 31, 1989.

He started his career at Aqueduct with none other than John Velazquez as his first jockey and retired sound after 53 starts (4 wins, 10 places, 5 shows. Career earnings $35,510, plus $24 we won at a dressage show last year). He first retired in 1994 but, so the story goes, whoever retired him ultimately gave up on re-breaking him and sent him back to the track. He retired again (for real this time) after two more races, at Suffolk Downs and Rockingham Park, in 1997.

Schmoopy catching some zzz’s at the 2011 American Eventing Championships.I will admit, I can’t say I noticed Schmoopy at all when I first met him. We were fixed up on a “blind date” by my then-riding instructor Gail Harrington when he was a school horse in her riding program at Black Magic Farm in Hampton, New Hampshire.

Schmoopy catching some zzz’s at the 2011 American Eventing Championships.I will admit, I can’t say I noticed Schmoopy at all when I first met him. We were fixed up on a “blind date” by my then-riding instructor Gail Harrington when he was a school horse in her riding program at Black Magic Farm in Hampton, New Hampshire.

Schmoopy doesn’t have much to recommend him and is not what you would call an “attention grabber.” He is an average height (16 hands), chronically underweight (the pickiest eater you will ever meet), ever-so-slightly-swaybacked, hay-dunker in a plain brown wrapper with absolutely no chrome, a small, misshapen star, a hind end so straight, he almost hyperextends through the hocks and he is over at both knees in the front. At the gallop he paddles along furiously in a workmanlike gait reminiscent of Seabiscuit (not in a good way). He is NOT a confident horse. He is plagued with almost debilitating fears of dogs, deer, plastic bags, blowing leaves, shadows, red horse trailers, white fences, and anything that looks out of place (or that isn’t in the same place it was yesterday).

However, he also has a nice, comfy, balanced gallop, a surprisingly scopey jump, large, kind eyes, and the softest nose you’ll ever kiss. He loves attention and has an inexhaustible tolerance for brushing, rubbing, mane-pulling, and generally being loved on. He vetted perfectly at age 10, coming 11. Now when people lecture me on the unsoundness of Mr. Prospector progeny, I just laugh and laugh.

Quiet partnership. Photo courtesy of Rachel Howell.He is the horse that sold me forever on off-track Thoroughbreds and motivated me to volunteer most of my free time with the Retired Racehorse Training Project (now Retired Racehorse Project), helping to incorporate it and serving for several years as an officer and director. I did nearly lose him twice to allegedly career-ending injuries and illnesses for which I was advised to put him down. But he battled back after protracted struggles both times to “recover 100%”. What can I tell you, the horse is All Heart.

Quiet partnership. Photo courtesy of Rachel Howell.He is the horse that sold me forever on off-track Thoroughbreds and motivated me to volunteer most of my free time with the Retired Racehorse Training Project (now Retired Racehorse Project), helping to incorporate it and serving for several years as an officer and director. I did nearly lose him twice to allegedly career-ending injuries and illnesses for which I was advised to put him down. But he battled back after protracted struggles both times to “recover 100%”. What can I tell you, the horse is All Heart.

He and I are an unfortunate pair in a lot of ways because we suffer from all the same weaknesses. He looks to the rider completely for guidance and to set him up perfectly for every fence, and unfortunately for him, I am not now, nor have I ever been that rider. I grew up as the Pony Club equivalent of a catch-rider, alternating between borrowed schoolmasters and totally inappropriate, barely-broken horses that I cowboyed around on insufficiently supervised until I had accumulated the world’s most defensive riding position and a lifetime’s worth of physical tension, mental baggage, and bad habits. It is hard to believe that, technically, I’ve been eventing since 1984 (yes, I pre-date body-protectors and beginner novice) considering how badly I still suck at it 30 years later.

I work full time as a trial attorney for the federal government, travel a lot, and commute around 2 hours daily so I am relegated to riding early mornings and late evenings, with inconsistent competition and lesson schedules. Periodically, I’ve enrolled Schmoopy in full time professional training including at some high-end dressage barns. Professional trainers’ initial reactions to Schmoopy invariably were “are you kidding me with this thing?” But in a barn full of fancy warmbloods whose attitude toward work could best be described as “cordially indifferent,” Schmoopy inevitably became the favorite because of his “Is it my turn yet? Pick me! Pick me!” attitude toward work and tremendous aptitude for improvement over time.

A better rider probably could have taken Schmoopy through Prelim, instead of toiling in relative obscurity at beginner novice, where we remain to this day. But I measure success differently with him.

Malinda and her boy at the AEC’s in 2011, when Schmoopy was 22. Photo by Mark Lehner, Hoofclix.For one thing, he’s an unbelievable trier. A flat-out “No” is not in his vocabulary. I have never encountered a horse so eager to please and so motivated by praise. He is also a highly accurate barometer for the quality of one’s riding. You get out of him exactly what you put in. With the benefit of a correct seat and aids, he earnestly cranks out a downright cute dressage test. The perfect, balanced gallop to the perfect take-off spot with plenty of reassuring leg from the rider produces about the most fun, clean, fast (beware of speed faults) cross-country round imaginable.

Malinda and her boy at the AEC’s in 2011, when Schmoopy was 22. Photo by Mark Lehner, Hoofclix.For one thing, he’s an unbelievable trier. A flat-out “No” is not in his vocabulary. I have never encountered a horse so eager to please and so motivated by praise. He is also a highly accurate barometer for the quality of one’s riding. You get out of him exactly what you put in. With the benefit of a correct seat and aids, he earnestly cranks out a downright cute dressage test. The perfect, balanced gallop to the perfect take-off spot with plenty of reassuring leg from the rider produces about the most fun, clean, fast (beware of speed faults) cross-country round imaginable.

But with even a momentary loss of focus on the rider’s part, it feels like a trap door opening up underneath you, as if there isn’t a horse there anymore at all. Amy Barrington, one of my favorite clinicians, once said to me: “when you feel that hesitation, he’s asking you a question. He’s asking ‘should we or shouldn’t we?’ And you have to answer him; immediately and affirmatively. “Yes. We can and we will.” Easily over 90% of everything I do know about riding I learned from him. You have to take responsibility for learning and practicing how to give him a good (enough) ride. You have to visualize success, find the confidence to hold out for it, and take it on blind faith that he really can do it. When you do, he never disappoints. Over the years, he has become desensitized to everything he used to be afraid of, which taught me a lot about the capacity of Thoroughbreds to learn and the value of persistence, patience, and practice.

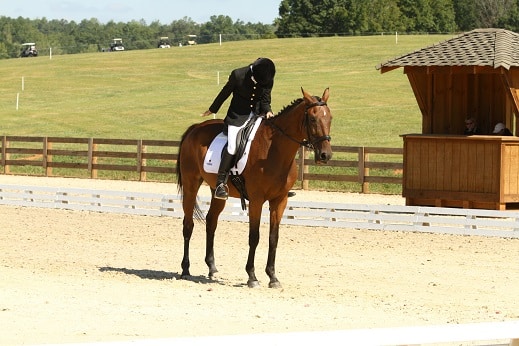

In the dressage ring. Photo by Mark Lehner, Hoofclix.Our range of activities is attributable to the fact that for most of our life together he was my only horse and thus stuck by default taking on every shiny, new equestrian adventure that struck my fancy. (And because he never really says no). My favorite thing to do with him is everything. He gives you the feeling that, against his better judgment, he’d carry you to the ends of the earth and hurl himself off the side if you put leg on and asked him to because you’re his person and he trusts you enough to do even things he’s afraid of.

In the dressage ring. Photo by Mark Lehner, Hoofclix.Our range of activities is attributable to the fact that for most of our life together he was my only horse and thus stuck by default taking on every shiny, new equestrian adventure that struck my fancy. (And because he never really says no). My favorite thing to do with him is everything. He gives you the feeling that, against his better judgment, he’d carry you to the ends of the earth and hurl himself off the side if you put leg on and asked him to because you’re his person and he trusts you enough to do even things he’s afraid of.

We’ve done dressage, long-lining, jumper shows, eventing, hunter paces, miles of trail riding, foxhunting, clinics with everyone you can think of, and even one particularly-memorable steeplechase clinic. He was SO good at the steeplechase it made me wonder if I’d missed his true calling in life – all the other horses running and jumping alongside was the confidence-booster he needed and he was UH-MAZ-ING.

Helmet cam video from Malinda and Schmoopy’s tour of Pimlico with fellow RRP-ers, Laury and Finley.This spring, we took part in Pimlico’s “Canter for the Cure” event that saw the track open up to let horses and riders of all ages, sizes and disciplines leave the starting gate and take a turn around the historic track that is the home to the second leg of the Triple Crown, the Preakness Stakes. Although Schmoopy is 25 this year, he was the one horse I wanted to have this experience with.

When we got on the track, his reaction to the starting gate was pure incredulity – as if to say, “are you sure you want to do that?” But like everything else I’ve ever faced him at, once persuaded that it really is what I wanted, he just shut up and did it.

After that, he was all business and knew exactly what he was doing. It was the opposite of every other experience we’ve ever had. No uncertainty, no hesitation, no looking to the rider for anything. Once we started galloping he shifted to auto-pilot. I wasn’t doing a thing – it was all just an experiment to me, to see what he would do. What he did was settle in to a perfect, rhythmic sort of stalking-horse gallop, and when his buddy started pressing him a little he just stretched out into this amazing-feeling racing gallop; so smooth and easy to stay with and yet so fast. He even swapped leads coming into the homestretch (I’ve never once been able to do flying changes with him in the dressage or show rings-go figure), and I could feel him reaching for the lead, expertly, and entirely of his own volition. There are those who say that horses don’t inherently love to run and indeed to race – but I’ll never believe it.

It felt like, on top of our 14 happy years of shared joy and mutual devotion and despite owing me nothing, he chose, of his own accord, that day to give me the most excellent, most magical, secret, special gift he had to bestow-to show me what it feels like to be Johnny V. How many people, how many off-track Thoroughbred owners even, ever actually get to experience that sensation of flying, fast-as-flames, on a perfect day, on perfect footing, around the far turn, down the stretch, to cross the wire first, at Pimlico, together, as one, with your very best friend in all the world…?

At Pimlico in May. “It felt like, on top of our 14 happy years of shared joy and mutual devotion and despite owing me nothing, he chose, of his own accord, that day to give me the most magical, secret, special gift he had to bestow ” Photo by JHA Photo Services.I think I love Schmoopy so much not because he’s this big, impressive-looking, talented athlete to whom everything comes easily, but because he isn’t. Everything we got, we got the hard way and every success is sweeter because we scratched and clawed our way through to it together.

At Pimlico in May. “It felt like, on top of our 14 happy years of shared joy and mutual devotion and despite owing me nothing, he chose, of his own accord, that day to give me the most magical, secret, special gift he had to bestow ” Photo by JHA Photo Services.I think I love Schmoopy so much not because he’s this big, impressive-looking, talented athlete to whom everything comes easily, but because he isn’t. Everything we got, we got the hard way and every success is sweeter because we scratched and clawed our way through to it together.

I love that RRP has succeeded in getting OTTBs back in the hands of some of the best trainers and competitors to bring renewed focus on the heights of athleticism of which they are capable. But a common misperception I still see is that owning or riding a horse off the track somehow requires special skills, facilities, or talent and so is reserved for a small minority of people.

While I agree horseownership in general is not for everyone, and requires commitment financially and otherwise, for those who really love horses, retired racehorses are in many ways the perfect horse for ordinary people like me. They tend to be less expensive on the front end. Soundness through a racing career appears, anecdotally at least, to bode well for long-term soundness post-racing as well. They already are pros at being clipped, shipped, shod, bathed, braided, wrapped, and all of the other daily life activities that can freak young horses (and their owners) out.

OTTBs like Schmoopy are versatile and capable of a far wider range of disciplines than a lot of people realize. They also are very people-oriented and exhibit a peculiar sort of loyalty and devotion in their relationships with humans that lends itself well to amateur or recreational horse owners looking for a longer-term relationship and to spend a lot of time with their horse, not just as a competitive mount but also as a companion.

Finally, Thoroughbreds are willing and forgiving and highly trainable, so even average or beginner riders who invest in training for the horse and education for themselves as riders find that a truly rewarding, truly fun horse of a lifetime, custom-fitted to one’s own ability level and choice of discipline, is much more within reach than many people think. Plus I have found that owning your own retired racehorse is just plain cool, and makes for great cocktail party conversation, especially at Derby parties.

If someone like me can own a Schmoopy, truly, anyone can.